Real Testimonials from Real Clients

Equine Veterinary Services

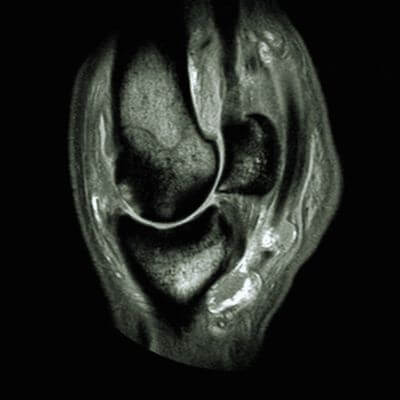

Equine wellness, lameness sports medicine, surgery, MRI, and more.

Online Pharmacy

Food, medication, and more with free delivery.

Equine Ambulatory Services

We come to you with our fully equipped mobile units and ambulatory vets.

About Blue Ridge Equine Clinic

Our board-certified equine surgeon and six ambulatory doctors make up our veterinary team at Blue Ridge Equine Clinic. Our services cover everything from routine equine health care to many types of equine surgery, lameness diagnosis and treatment, arthroscopy, upper respiratory procedures, and other soft tissue and orthopedic treatments. Established in 1979, Blue Ridge Equine Clinic is a full-service equine veterinary clinic serving Central Virginia.

Complete Equine Veterinary Services in Earlysville, VA

Our services cover everything from routine equine health care to many types of equine surgery, lameness diagnosis and treatment, arthroscopy, upper respiratory procedures, and other soft tissue and orthopedic treatments.

Our Equine Veterinary Team

Our board-certified equine surgeon and five ambulatory doctors make up our veterinary team at Blue Ridge Equine Clinic. Our ambulatory veterinarians serve Albemarle and its surrounding counties and beyond. Blue Ridge Equine Clinic clientele come from all over the Mid-Atlantic region and range from cherished equines to top-performance horses in all disciplines.